On Friday, September 14, 2012, Gwen Westerman and Bruce White spoke before an audience at the Bookshelf, an attractive bookstore combined with a cafe, close to the Mississippi River in the city of Winona. This city is the location of one of the village sites occupied by the Kiyuksa band of Dakota under the leadership of the series of Dakota chiefs known as Wapahaśa, or Wabasha.

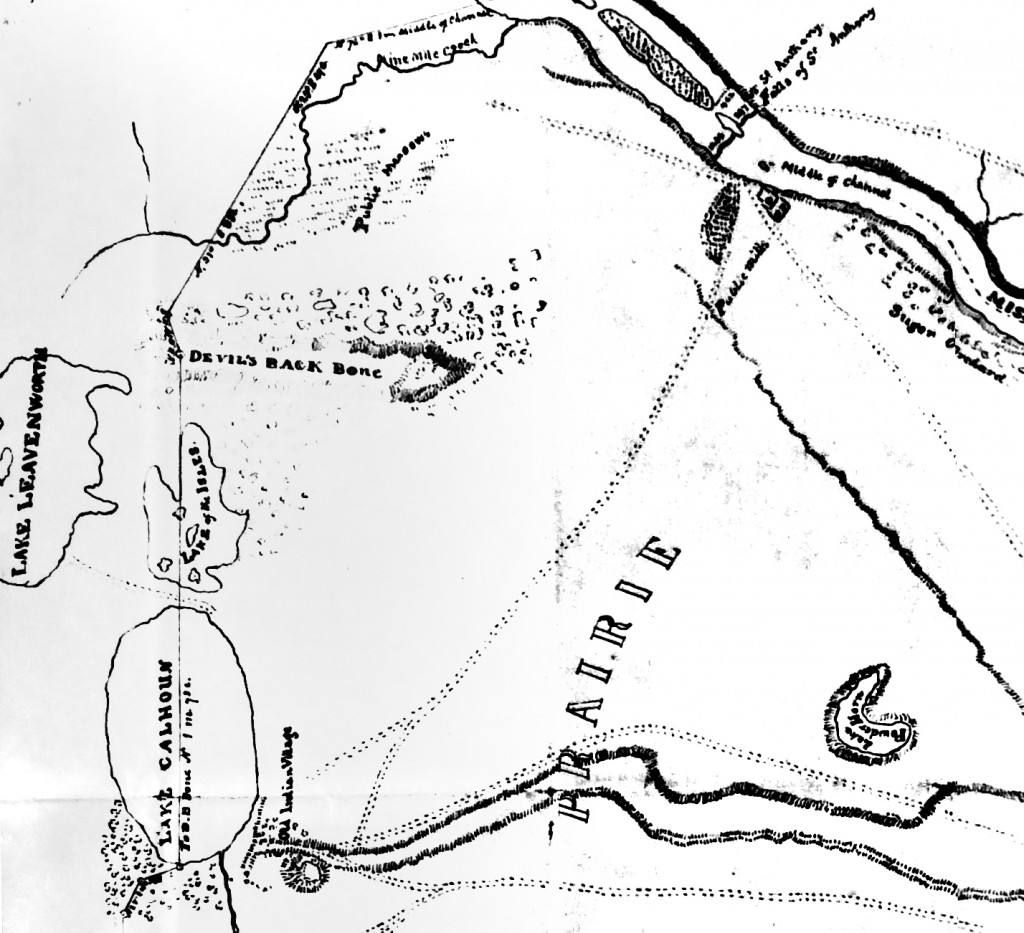

A view of “Wabashaw’s Prairie” by artist Seth East, around 1847, look from the Mississippi River toward the nearby hills. The original is in the Minnesota Historical Society.

Among those in the audience were a group from Rochester, Minnesota, who are supporters of the preservation of Indian Heights Park, a beautiful park along the Wazi Oźu Wakpa, now known as the Zumbro River, which is the recorded location of Dakota burials dating as late as the 1850s. Their presence brought to mind a story recorded about Winona in Chapter 3 of our book (page 131) about how the grave sites of members of Wapahasa’s band were protected by early settlers of the city. The following account is one we quoted from an early history of Winona County. It ought to be an inspiration to people today, to protect the burial sites–and the ancient cultural sites–of the Dakota which still exist all over the region of Mni Sota Makoce today.

Quite a number of Indian graves were on these grounds. Nearly in front of the farmhouse there were two or three graves of more modern burial lying side by side. These were said to be the last resting-place of some of Wabasha’s relatives. The Sioux made a special request of Mr. Burns and his family that these graves should not be disturbed. This Mr. Burns promised, and the little mounds, covered with billets of wood, were never molested, although they were in his garden and not far from his house. For many years they remained as they were left by the Indians, until the wood by which they were covered rotted away entirely. A light frame or fence of poles put there by Mr. Burns always covered the locality during his lifetime.